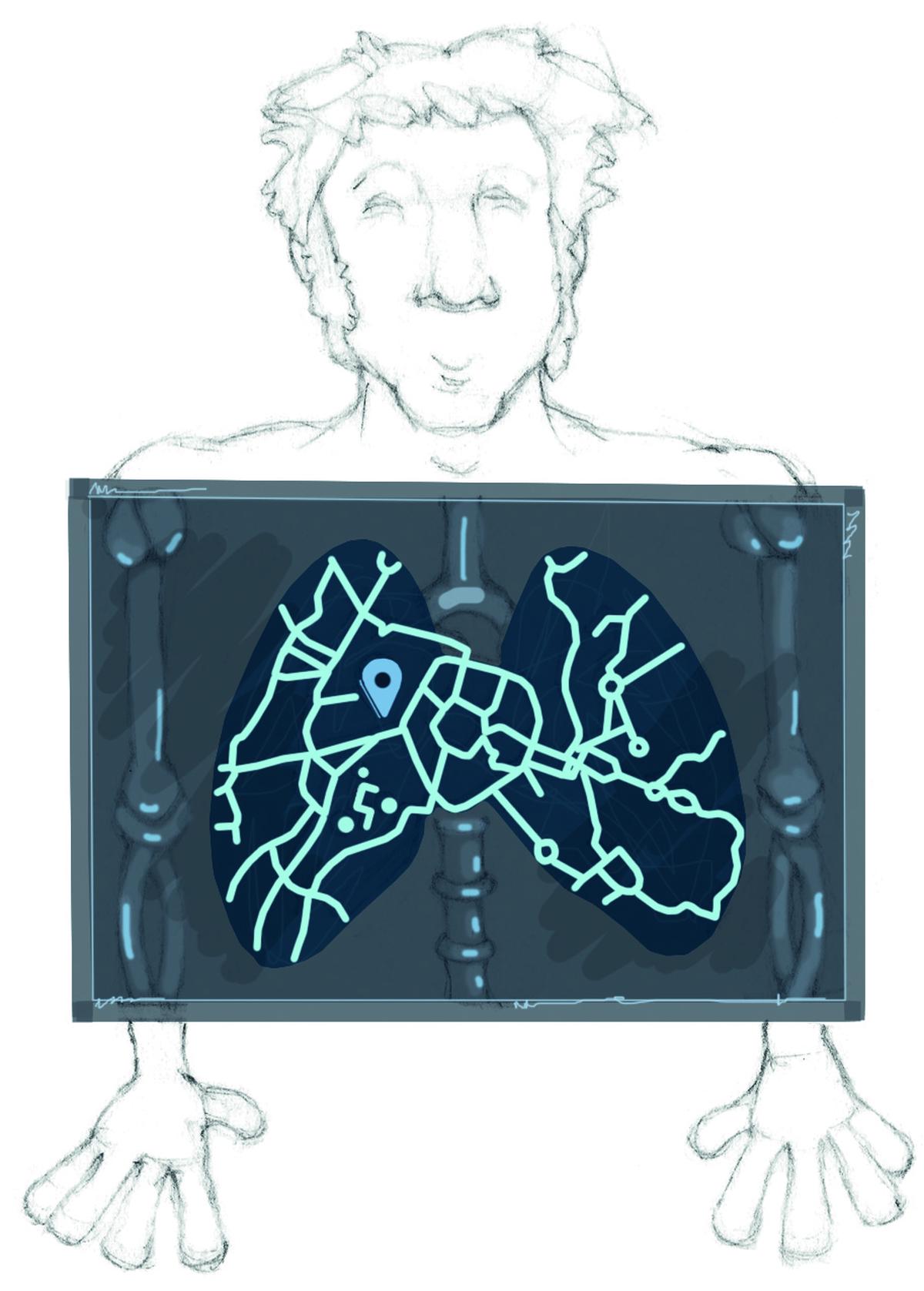

The AirCasting platform is used by individuals, communities, and institutions around the world to measure air pollution. In a recently published article, Nicola da Schio, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cosmopolis Centre for Urban Research of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), reflects on the lessons from an AirCasting project that rolled out in Brussels between 2016 and 2019 as a collaboration between academics at VUB, staff from a local NGO, and community volunteers.

Citizen science can be a tool to democratise societies by empowering citizens and opening up the governance of technical issues to lay persons. To analyze whether and how citizen science can empower communities I analyzed AirCasting Brussels, a citizen science project that was run in Brussels between 2016 and 2019 that utilized AirBeams and the AirCasting smartphone and web apps. The project was led by VUB in partnership with BRAL Citizens Action Brussels - a community based organization working on issues of urban democracy, empowerment, and sustainable urban development - and various groups of citizens that were invited to join the project. As part of the project, participants were directed to form groups (e.g. of neighbours, colleagues, friends, parents) and participate in a series series of workshops for six-to-eight months. During the workshops, participants were encouraged to share their experiences and interests, ask questions, and try to respond jointly to them. In addition, they created maps and graphs to visualize their air quality data and teach others about their findings, organised public events to share experiences and raise raise awareness, and worked to engage with policymakers on the topic of clean air. The project contributed to a wider mobilization for cleaner air that involved numerous citizens groups, NGOs and researchers, and culminated in the organization of Brussels’ first General Assembly on Air.

But did the project empower participants? if so, how?To respond to these questions, I started by exploring the literature about citizen science, social movements, and empowerment. The first thing that emerged is a definition of empowerment that is generative: in order to participate from a position of greater strength in decision-making and influence such decisions, empowerment needs to be understood as a process by which people become aware of their own interests and how those interests intersect with or conflict with the interests of others. Secondly, I identified three processes through which citizen scientists can be empowered: gaining knowledge, gaining epistemic recognition, and building relationships. The extent to which these processes take place will tell us whether citizen science exercises are truly empowering.

> Gaining knowledge. First, citizen science worked as a learning device. This happened in multiple ways including direct measuring, experience sharing, and exchange between citizens and academia. The fact that Brussels is polluted has been known for a long time, and the project did not produce ground-breaking results in that respect, yet citizen science made visible what was hidden in labs and mathematical models and contributed to making it part of the public debate.

> Gaining epistemic recognition. In layperson words, this means that a person’s voice and perspective over an issue gains recognition. In this, I observed mixed results. AirCasting Brussels was surely successful in giving voice to new actors and in developing an innovative way to understand the pollution problem. At the same time, communities’ role as actors within the air pollution debate remains challenged by the status quo, which elevates the voice of regulators, scientists, and industry above those of community members.

> Building relationships. Regardless of how it is generated and disseminated, knowledge alone is rarely sufficient to bring about change. AirCasting Brussels was part of and contributed to developing networks of interaction between people and institutions. It contributed to weaving together relations between research and activist communities, which may be a game-changer in the context of future air-pollution monitoring and decision-making processes.

Citizen science should not be uncritically ascribed as the silver bullet that empowers all those who engage with it, not the least because of the sheer variety of projects and initiatives that exist. At the same time, it does carry a great potential if a project is well designed. As a counterpart to their fundamental right to participate in democracy, citizen science can be effective to strengthen citizens’ capabilities to do so in a meaningful manner.

To read more about this story:

The Empowering Virtues of Citizen Science: Claiming Clean Air in Brussels https://estsjournal.org/index.php/ests/article/view/795 » this article expands and develops the reflections included in this blog post

Self-Portraits of Personal Exposure to Air Pollution: on where and when People Are Exposed, and on why it Is Difficult to Avoid https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-020-00176-y » this is an article on personal exposure to air pollution that was published as part of the project

Citizen science. Collective knowledge empowers https://bral.brussels/nl/artikel/citizen-science-collective-knowledge-empowers » this is an illustrated booklet by BRAL & VUB that explains in detail the whole AirCasting Brussels project, and puts forward drawing and thinking about active citizenship and engaged research

Image Credit: CC BY NC ND Eloïse Vanhouteghem www.oisele.com